Hartley News Online Your alumni and supporter magazine

From 1950 to 2015, general election turnout has fallen by nearly 20 per cent. Alumni Jason Cowley, editor of New Statesman, and John Denham, former MP for Southampton Itchen, discuss the mood of anti-politics in the UK, and how to re-engage the electorate.

Jason Cowley (BA English and Philosophy, 1989) editor, New Statesman: When people believe that something matters and there are real issues at stake, the result can be extraordinary engagement. Look at what happened in Scotland during the referendum campaign. The future of Scotland and of the United Kingdom were at stake, and people of all ages responded with great interest.

However, there is perhaps something about the way mainstream politics is conducted at Westminster that doesn’t quite ignite people’s interest. That might come down to the professionalisation of politics. Many of our leading politicians come from a very narrow social and educational background. George Osborne talks of the “guild” of professional politicians, of which he is a part, as are many others, such as David Cameron, Ed Miliband, Ed Balls, Nick Clegg and so on. By that, Osborne means politicians who leave Oxbridge, work as special advisers to politicians, progress to safe seats, and are fast-tracked into the cabinet. That process creates a type of identikit professional politician from whom many people feel alienated. There is a sense that these politicians know little of the world outside Westminster or Whitehall.

I am also struck by how narrow and parochial the election campaign was. None of the party leaders were talking about foreign affairs or Britain’s role in the world and that was a significant miss. Whatever your views are on Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair, they were genuine national leaders with vision and the acumen required to command a significant majority.

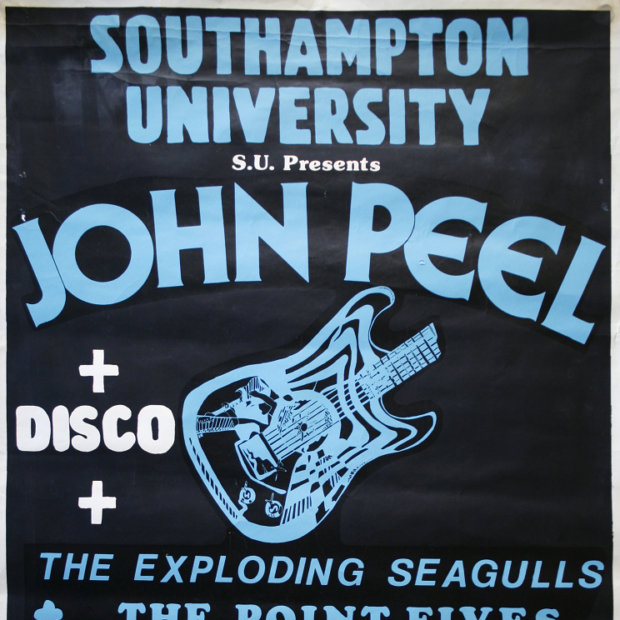

My time at Southampton coincided with the Thatcher boom years. The first election in which I voted was the Conservative landslide victory in 1987. Most of my fellow students voted Tory and the main opposition to the student Conservative club at the University was not Labour but the far left Socialist Workers Party. The students’ Labour group had very little presence on campus, which reflected the mood nationwide. Even then, in the late eighties, among the student population, there wasn’t a great sense of political engagement or idealism, which surprised me. A lot of people I knew wanted to work in the City for one of the big banks or become corporate lawyers.

A change in the voting system might engage more people. Our “first past the post” system means that too many of us live in safe seats. If you live in a safe seat (of which there are 400+) and want to vote against the incumbent, your vote is almost meaningless. However, under proportional representation, your vote would at least count in a way it cannot at present, and political parties might be more inclined to work harder for that vote. I live in a safe Tory seat and I did not have one leaflet put through my door or see a single Labour candidate out on the street. If it was a marginal seat, there would have been a lot more activity. You would have felt something was at stake.

Politics is among my primary interests yet I also accept that many people are simply not interested in the day-to-day activities of Westminster. Do I support compulsory voting, as in Australia? I don’t think it should be a stipulation of the state that you vote. You should have the freedom not to vote if you wish not to do so. But given that so many people struggled so hard to enfranchise the majority, I think people ought to vote. If no one party appeals to you, then spoil your ballot paper as a mark of protest. Above all, make the effort to understand the issues and to work out what you think about them.

John Denham (BSc Chemistry, 1974), former MP for Southampton Itchen, and parliamentary private secretary to Ed Milliband: I would challenge those who say there is no point in voting. They are profoundly wrong. There is a moral obligation to respect the democratic process and to understand that it is a precious thing and that any other way of changing society will be worse. That said, the point about democracy is that you have a choice as to both who you vote for and whether to vote. The idea that you are in a democracy where you don’t have a choice seems to give rise to a contradiction. The challenge behind increasing voter numbers is establishing a connection between someone voting and something changing as a result. With a programme like the X Factor, you can see before your eyes how the votes mount up for certain candidates and who has won. Voting in a parliamentary or council election isn’t so straightforward. When I started in politics 30 years ago, it was much more common for someone to say, “I will always vote Labour, that is the party for someone like me.” If your ‘team’ was running the country, you could be reasonably comfortable that they would give you a better deal than the other team would. But the notion of class blocks and people seeing a political party as representing their section of society is much less well-established now. People can’t vote for their team and feel they are likely to have the best possible result. They want to see change coming from their vote and that is hard for politicians to establish. People also need to feel that there is something at stake.

If people think that there are genuine issues, they will queue for hours in the baking sun in order to cast their votes.

In that sense, enabling people to vote online, or having fixed-term parliaments allowing greater election build-up, or lowering the voting age, won’t make the slightest difference. The evidence from the Scottish referendum was not that lowering the voting age suddenly made a whole generation interested in politics. It was that the devolution campaign seemed to be about something quite profound. If politicians don’t manage to establish that there are some big options in front of people, then lowering the voting age will simply extend the age at which fewer people vote. Politicians do need to help themselves. There are political activists my age who think that the media is the News at Ten, or reading the Guardian or Telegraph. I have to explain that half the electorate never watch the news and don’t read a newspaper in a paper form. Technology has to reach voters in all the places they expect to receive information, to receive opinion and be able to contribute to it. Political parties that don’t do that will fail.

You omit to mention that John Denham was a cabinet minister who had the courage and principles to resign over the Iraq War. On the question of engagement in politics, there are interesting lessons to be learnt from the success of Jeremy Corbyn in the Labour leadership contest. These lessons are not about nostalgia or burying one’s head in the sand, but about welcoming the refreshing sight of a politician a who actually seems to believe in something and to speak in normal language.

Politics is about power and and who shall wield it.

When mainstream politicians and institutions complain about anti-politics: what they really mean is why aren’t they voting for us? And they are not voting for you because of what you have done

It would be instructive to compare what has been done in this country to working class communities in the last 50 years, with what was done in South Africa under the Group Areas Act; and to compare the sense of loss and grief displayed by the victims at the trashing of their respective communities.

Great outrage was displayed in the 1960’s, at the District Six removals in Capetown, South Africa. On 11 February 1966, the South African Government

declared District Six a whites-only area under the Group Areas Act, with

removals starting in 1968. By 1982, more than 60,000 people had been relocated

to the bleak Cape Flats Township some 25 kilometres away. Everything in

District Six was bulldozed except a couple of churches. The people that were removed suffered incredible cultural and identity loss and were subject to the appalling violence of the Cape Flats criminal gangs.

The working classes in this country after 1950 saw their families dispersed, their towns and close knit communities destroyed and turned into murderous, vice ridden slums infinitely worse than anything they replaced, a thing that even the Luftwaffe did not achieve. Their family oriented culture came under constant and consistent attack. The abolition of capital and corporal punishment was something they never wanted because they knew what it would mean for them. The schools which offered a way out of poverty were debauched and an anti-learning culture fostered from within them. They were called “chavs” and made to feel that their culture and love of country was inferior and even the traditional recreations of pub smoking with a drink outlawed.

The responses to both of these events were very different. The one elicited outrage; but protests against the other were regarded with incomprehension

and contempt. It was as if society regarded the working classes in Britain to be of a lower order that was unable to experience emotion and loss; a brute order of humanity with a debased culture of no value. The enormity of what has been done to British society in the name of social engineering is now beginning to sink in. We get calls to fix our broken society by the very people who broke it in the first place. Like post Apartheid South Africa, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission should be set up, where the enforcers are encouraged to admit that everything they have implemented in the name of social engineering in the last fifty years has been a giant, tragic, cruel, wicked and traumatic social experiment inspired by some very base motives. Those who do not come from these communities do not even begin to understand the depth of the contempt and anger. People justly feel betrayed and marginalised by the very organizations that should have protected them.

I was born in the East End of London and I saw it happen; it was my aunts, my uncles, my family and my community that was smashed. Like the Jewish poet Emanuel Litvinoff; when I return to the East End all I see are ghosts. I was also in Capetown when the removals from District Six took place; the same rejection and the same betrayal. I am happy to say that I still have good friends there. So I retain the right to make these comments no matter how unwelcome they may be; there is a world of difference between being there and experiencing it, and just reading about it in books.

The society and communities in Britain that were displaced were not perfect by any means, but in comparison to the violent and dysfunctional chaos that has been brought about by the activities of politicians and their enforcers, it was a heaven of tolerance. That society was no accident; it was brought about after a 100 years of social reform by the Victorians and Edwardians. And our murderous and vice ridden society is no accident either; it was brought about in 50 short years by

agents of a force bent on our destruction. They have managed to achieve the almost impossible; they have dragged us back into the horrors of the 18th century. Our unwritten constitution worked very well until recently, but it afforded us no protection from an internal enemy, not based on Plato’s Will to Good, but based on Nietzsche’s Will to Power. And God help us, we let it happen. What has been done is wrong in Christian terms, in philosophical terms, in human terms and in terms of self interest.

Normal human relations are rooted in mutual respect not in the hatreds of domination by intolerance.

There are many reasons for what is a profound disconnect between the electorate and our elected politicians. Much of national and international politics has moved away from the nation-state, for the UK that means largely the European Union. Local government has steadily diminished in England as Whitehall-Westminster have centralised more powers. Alternative methods have developed, notably single issue campaigning and of late petitions via social media.

Long before UKIP’s increase in support and in Scotland the SNP achieving power – the electorate, especially those in England – found ALL elected politicians unresponsive to their views and wishes. Over what? Hanging at one point (opinion has now shifted to being anti). Immigration and truly restricting it. The increasing role of the European Union. Above all I suspect the biggest reason is seeing how ineffective government was in achieving results for them.

At the national level it is easy to get the view politicians live in their own world, secure in the Palace of Westminster and nearby. Along came the scandals around parliamentary expenses and just a few days ago MPs getting a 10% rise in salary, when many in the public sector were told 1% is for you. Politicians who seem far more comfortable with focus groups, opinion polling and each other. Our electoral system helps to reinforce the status quo.

David Page, BSc Politics & International Studies 1979 and John’s successor as Union President.

It is ….. curious ? instructive ? that neither writer in

this piece sees fit to mention that, in polls of trustworthy jobs, politicians

and journalists are always jostling for last place with estate agents, car

salesmen and bankers.

Perhaps

the venality and selfishness demonstrated by the expenses scandals, the brown

bag payments, the Speaker’s expenses reported today, the freebie trips and

meals, cronyism and so on have something to do with it ?

Neither

do they mention the lack of engagement in local politics, which can (I suggest)

be ascribed to the same reasons, plus amateurism and incompetence – at least

when MPs get their snouts in the trough they do it thoroughly..

…. and why does anyone think journalists are any better/more intelligent/more honest/more competent than politicians ?