Hartley News Online Your alumni and supporter magazine

Since the discovery of the first true antibiotic, penicillin, in 1928, we have used these medicines to cure illnesses, treat infection and save lives for ninety years. Now it seems the golden age of antibiotics is about to come to an end.

Overuse of the medicine, especially for non-serious infections and agriculture, has caused the drugs to become less effective, and we are now facing the consequences. Antibiotic resistance is on the rise, and infections which until now have been easily treatable will increase in threat.

At the end of 2017 the Office for National Statistics stated that antibiotic resistance has caused a fall in life expectancy for the first time. If this situation continues, infections and illnesses that would previously have been curable by antibiotics will kill more people worldwide than cancer by 2050.

Scientists and researchers at the University of Southampton are joining forces across disciplines to combat the risks of antibiotic resistance, searching for alternatives and exploring ways to prevent infection in the first place.

Within these teams are some of our own graduates. Southampton alumni Dr Thomas Secker (PhD Biological Sciences, 2012), and postgraduate research student Freya Malcher (MEng Acoustical Engineering, 2017), are doing their bit to beat microbes at their own game.

Infection prevention

While a large amount of Anti-Microbial Resistance (AMR) research is focused on finding antibiotic alternatives, Thomas and Freya are working on projects that will help to prevent infection in the first place. A decrease in infection rate leads to a lower demand for antibiotics, therefore slowing down AMR.

“If bacteria keep becoming resistant and we don’t find new antibiotics, a simple thing like going to your doctors with a minor bacterial infection or, having routine surgery could actually kill you,” says Tom. “The discovery of new antibiotics is currently decreasing and the prevalence of infections by bacteria resistant to all antibiotics is on the increase.”

We are looking at ways to prevent infections in the first place; if we can slow that whole process down by stopping microbes infecting a person using more effective ways of cleaning wounds, for example, it will be a huge help in the race against AMR.

Tom and Freya are both working with Professor Tim Leighton and his original invention of StarStream to prevent infection by deep-cleaning surfaces, wounds and infected materials.

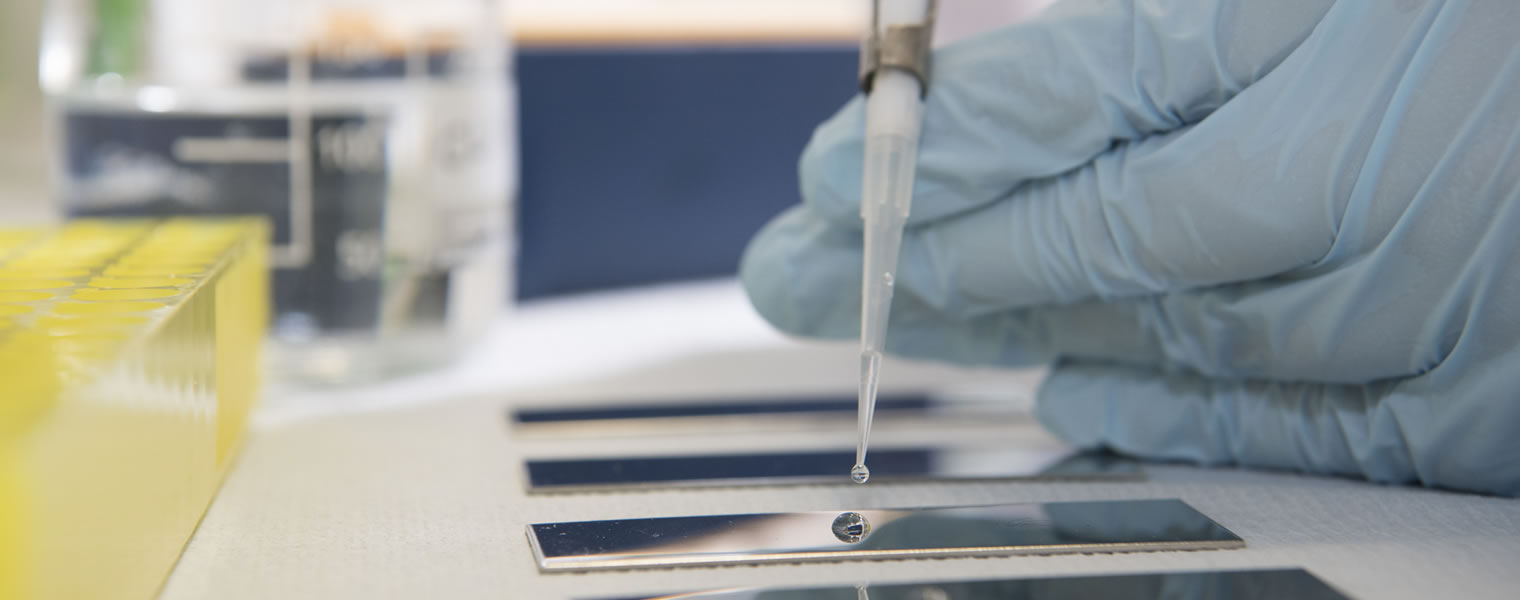

Thomas explains: “StarStream uses ultrasound to make bubbles resonate, and those shaking surfaces on the bubbles cause shear stress which acts like a gentle scrubbing motion. It’s an extremely effective cleaning method without the use of chemicals or additives and the need for hot water, so it’s environmentally friendly too.”

Tom also works with Professor Bill Keevil in Biological Sciences, exploring acoustical technologies for cleaning surgical instruments and endoscopes in hospitals thanks to a £817K grant from the National Institute for Health Research, Central Commissioning Facility, Policy Research Programme (NIHR CCF PCP).

By using Tim’s StarStream technology in hospital sterilisation departments, they are hoping to revolutionise how surgical instruments are washed. The ultrasonic technology is much more efficient at removing microbes and proteins that are hard to clean, therefore reducing the risk of infection.

Tom has been working with Bill since he became a research technician at the University prior to his PhD, and throughout his postgraduate degree, and Tom is now jointly working with both Bill and Tim, who he credits with motivating him to influence policy in the wider world.

“That’s something that Tim and Bill have taught me very well; what’s the point of doing research that’s not going to get used? We’re working with companies who will be able to build and translate these devices as soon as we have them ready to put out there.”

Bringing biology and engineering together

Freya’s interest in ultrasonics began during her third year of her undergraduate degree here at Southampton, when she worked with Tim to use StarStream technology for floor cleaning. This was a major influence on her decision to continue as a postgraduate student.

She is now working with industry to use the StarStream technology to combat infection. Her expertise in engineering means that she is working closely with other teams to cover all areas.

“Working in a team like this pulls everyone’s knowledge together,” she says.

We’ve got people with electrical backgrounds who can help with the electronics of these projects; there are acoustical engineers like me who can work on the acoustics, and biologists too. We really are bringing everyone together, mixing in and transferring knowledge between each other

“In my research I have to think about how you can make a device that people actually want to use. AMR is important and something needs to be done. I suppose doing a PhD in this area is actually helping the world a little bit, and combatting issues that we need to really think about. If we don’t do something about it now, who knows what could happen in twenty years.”

Tom and Freya are also involved in the University’s Network for Anti-Microbial Resistance and Infection Prevention (NAMRIP), which brings disciplines together to tackle the major issues surrounding AMR and infection. NAMRIP has won awards for its public engagement over the last two years; part of this activity involves educating people about the risks of AMR and what they can do to help. The University of Southampton is also leading the new National Biofilms Innovation Centre (NBIC), further strengthening our research into AMR.

“We work on making really difficult concepts simple to understand,” says Tom. “For example, we’re teaching the public that if you have the flu, you don’t need to take antibiotics because it’s a virus. This will help us to avoid putting a strain on the doctors or relying on antibiotics and thus contributing towards antibiotic resistance. Trying to change those perceptions is so important.”

If we keep using antibiotics the way we are using them, we’re putting ourselves in danger. That’s why I study ways to improve infection prevention; if we can stop people getting the infection at stage one, then we don’t need to rely on antibiotics.