Hartley News Online Your alumni and supporter magazine

For the past 30 years, the UK has marked Black History Month in October to highlight and celebrate important people and events in the history of the black community.

Remembering the victims of slavery – celebrating their endurance and resistance – is central to Black History Month. But Southampton’s Christer Petley, Professor of Atlantic History, explains how making sense of slaveholders can offer another extremely important way of understanding slavery and its bitter legacies.

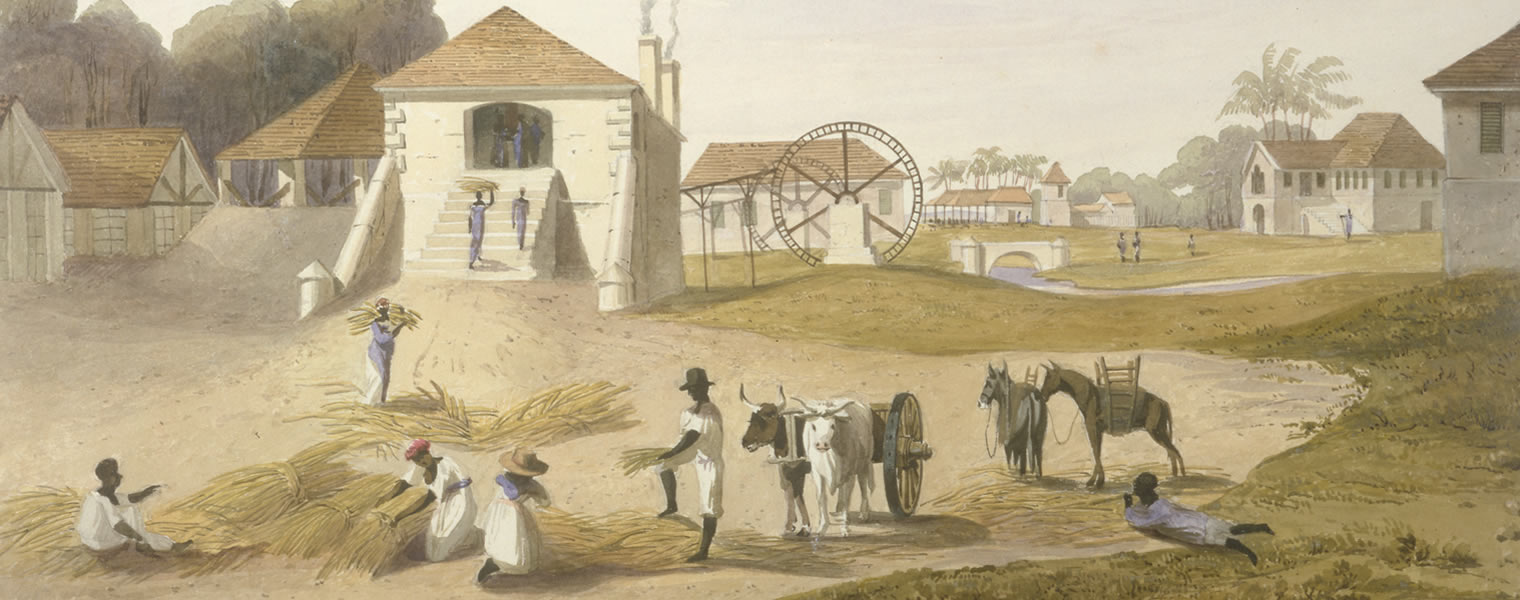

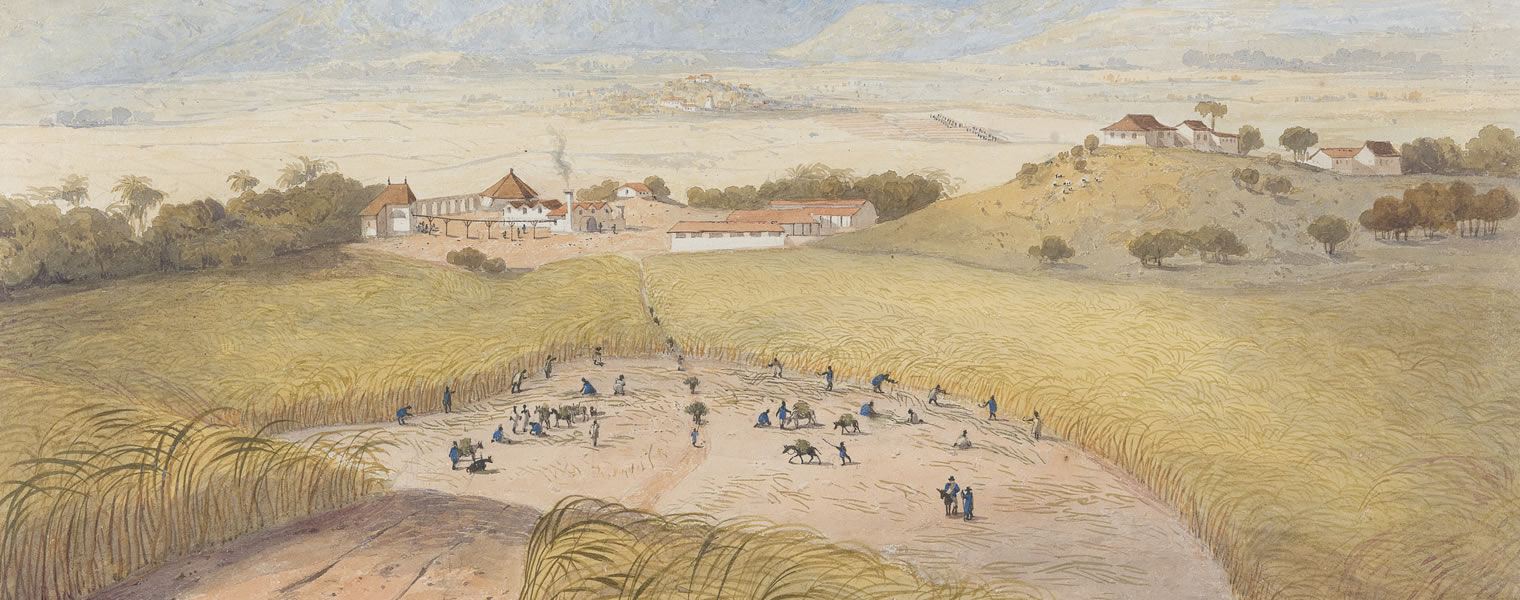

My research explores the histories and legacies of slavery in the Americas, focusing on slave societies in the Caribbean. Most recently, I have been studying a white slaveholder called Simon Taylor, who was one of the richest Britons of his era. Taylor lived in the colony of Jamaica, where he owned three large sugar estates. He also claimed ownership over thousands of girls, boys, women, and men: these were the people forced to live, work, and die on his properties as slaves.

By 1807, Taylor’s anger was running hot; he was approaching the age of 70 and the abolitionist campaign, which he had vehemently opposed for decades, was on the brink of its first major success: the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade.

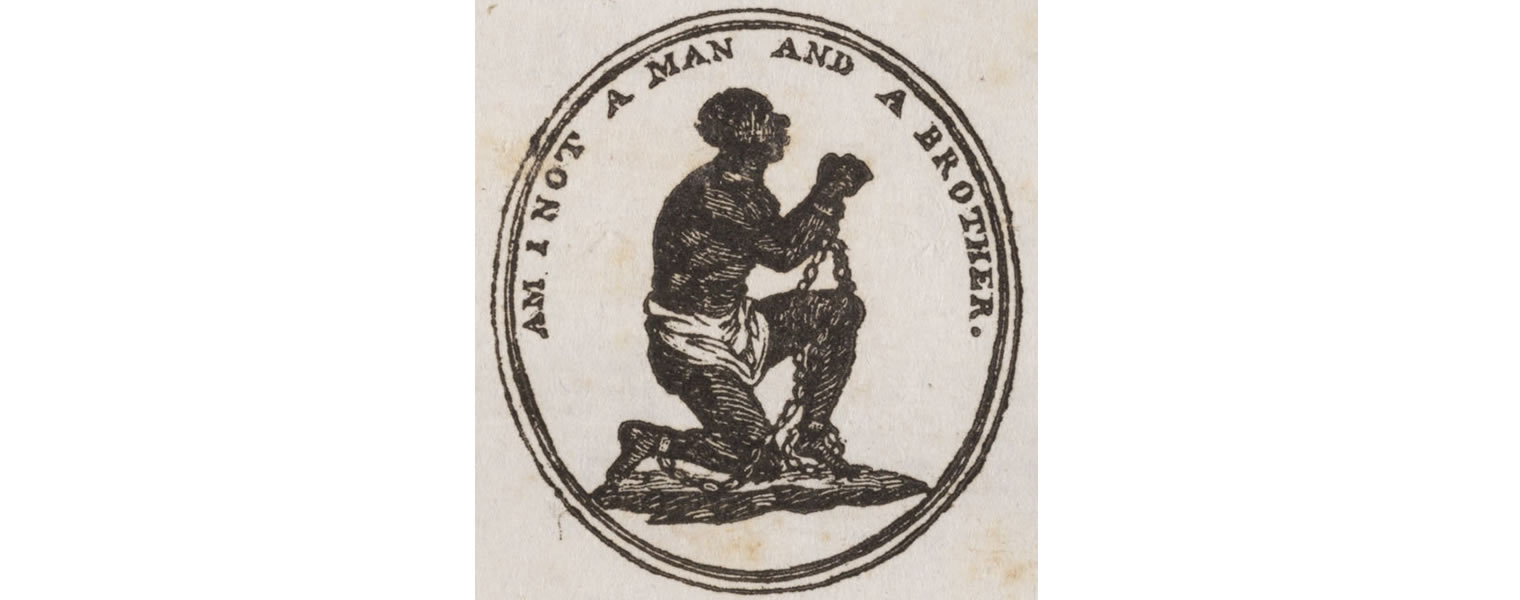

‘Am I not a man and a brother?’ was the slogan of the abolition movement, always accompanied by the iconic image of a kneeling African. It was an image and message that grabbed public attention and changed perceptions. But to a man like Taylor, it simply stoked fear, frustration and fury.

When parliament, responding to the abolitionist campaign, finally agreed to end the slave trade, Taylor was ‘lost in astonishment and amazement at the phrensy [frenzy] which has seized the British nation’.

My research on Taylor and his letters has led to my recent book, White Fury—about slavery in Jamaica and the fierce political conflict over the future of the institution in the British Empire, including the part that Taylor played in those struggles.

But why pay such attention to a racist white slaveholder like Taylor, rather than the victims of slavery, you may well ask? I don’t see the critical analysis of slaveholders as being opposed to the study of slaves. Rather, those two things represent two aspects of the same problem.

It is necessary for us to try to make sense of what the slaves faced, and to do that, it is necessary to study people like Taylor.

The legacies left behind by slaveholders provide another set of reasons. Former slaveholders clung to their wealth, which flowed into the wider British economy. Their racist ideas persist too.

Making sense of those things provided the rationale for White Fury and helps frame how I teach these subjects. My third year special subject module concentrates on Slavery and Freedom and is just one of a number of modules at Southampton that focus on an element of black history.

My desire to understand the world of the slaveholders and its legacies has also influenced my recent collaboration with the performance artist Elaine Mitchener. Elaine has produced an experimental and ambitious piece of music theatre Sweet Tooth, which stages a dramatic engagement with the brutal realities of the sugar industry and slave resistance, making use of some of the same historical documents – such as Taylor’s letters – that I used in my research for White Fury.

It has been a privilege to write White Fury, to discuss Taylor and his world with students, and to collaborate with Elaine on Sweet Tooth.

I am convinced that trying to understand greed, cruelty, fear, and fury in the past can help us to understand the survival, or re-emergence, of those forces in the present. And despite the challenges we now face, I still cling to the hope that such knowledge can help us to create a brighter future.

Find out more about Christer and his research.