Hartley News Online Your alumni and supporter magazine

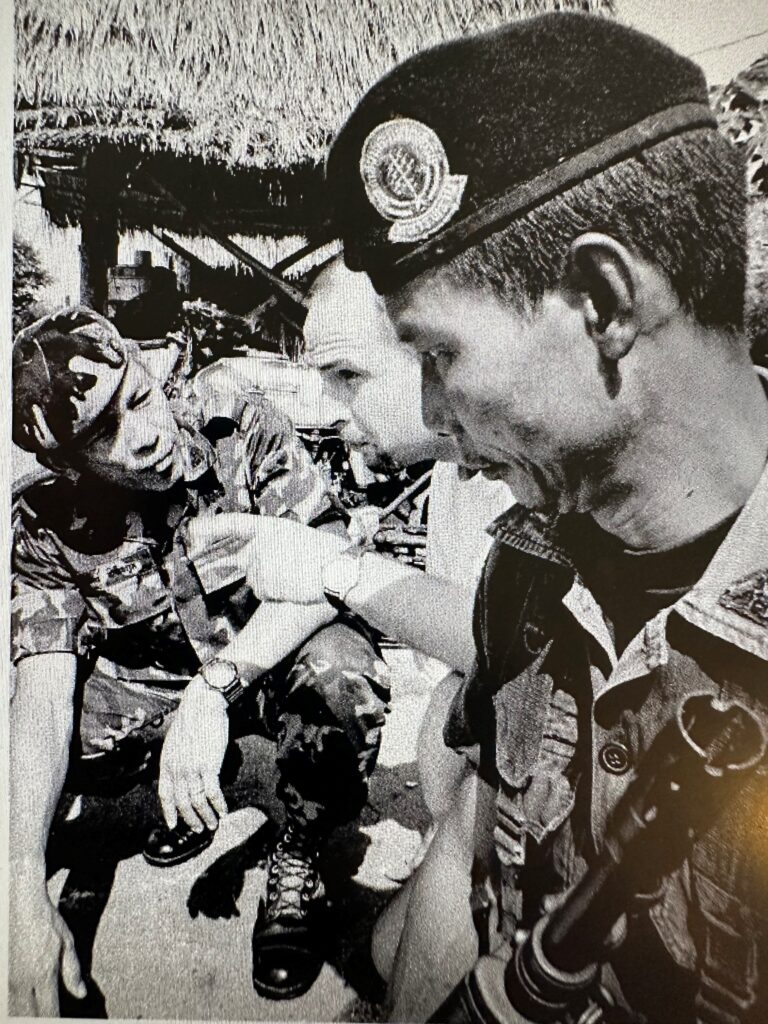

Dr Guy Rhodes (PhD Geophysical Science, 1994; BSc Oceanography, 1990) is an international specialist in humanitarian demining. His 30 year career spans over 35 countries, and has involved working in some of the world’s most challenging humanitarian environments.

Guy spoke to Hartley News Online about his many adventures, and the highs and lows of this important and fulfilling career.

“I think a milestone moment in terms of humanitarian demining was Lady Diana, in those famous photographs, standing in a minefield wearing the logo of The HALO Trust, the biggest demining NGO around.

I worked for them first during my PhD at Southampton not long before those photos were taken. I spoke to my supervisor, took a break and worked for HALO for six months in Mozambique as part of a project for the UN. There were two or three million refugees in Malawi and in Zimbabwe and we had to survey the landmines and map the roads that were safe to help the repatriation effort.

I came back and finished my PhD but my path had been set. I ended up working in the demining profession for 30 years.”

Landmines are one of the most destructive long-term remnants of war, and disproportionately affect civilians, rather than military personnel. Many minefields continue to claim victims decades after the conflict has ended.

“After a conflict has finished, when a country needs to get back on its feet, refugees and internally displaced people need to go home: they need to rebuild their lives and communities.

“They go back. They have terrible accidents. Because of the mines they can’t build or rebuild houses, cultivate the land or reestablish themselves.

“Sometimes access to wells and water sources, roads and infrastructure is blocked and reconstruction is hampered because explosive devices – the presence (or fear) of mine contamination – can just disable a whole region or country.”

An early pioneer

When Guy started working in humanitarian demining in Mozambique, it was new field, with few established standards, practises or safeguards.

“There wasn’t much supervision and I was given lots of responsibility without much communication. This was before email was routinely used and fax was our means of communication. The sector as it is today simply didn’t exist at that time.

“It’s now built into quite a big industry, one that’s had an enormous impact on reducing mine-related accidents.

“Now there are standards and equipment. There are procedures that you have to follow and it’s all much safer and more organised. It’s all about being prepared and being in the right place at the right time to facilitate reconstruction.

“I feel privileged to have been at the forefront of building this sector up and enabling it to grow.”

Travelling the globe

Guy’s work has taken him from the African bush in Mozambique and Angola, to the borders of borders of Thailand, the shores of Sri Lanka and to roles at the heart of the United Nations in Geneva.

“In Thailand I was surveying the borders with the Thai military and a team of 200 people. We mapped 5700 kilometres of borders areas with Malaysia, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar: this was part of the obligations that Thailand had on signing the International Convention to Ban Landmines.

“We were in places that tourists weren’t permitted to go, working along the border areas controlled by the military. There were lots of accidents associated with cross-border criminal activities: transfer of stolen vehicles, drugs and illegal logging.

“After Thailand, I went to Vietnam, working for the Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation. It was all about rebuilding the relationships between Vietnam and the US.

“The Memorandum of Understanding with the Ministry of Defence of Vietnam alone took three and a half years to agree and had 34 different versions due to the suspicion between the two former warring parties.”

A breadth of humanitarian work

“I went from Vietnam to Sri Lanka. When the tsunami hit, I was there within the week.

“After a disaster, demining organisations can be crucial, because you’ve got hundreds of people with vehicles, trucks and water: lots of resources and people, organised into units. There was the clean up to be done, bodies to be collected on beaches. There were some complicated demining needs because the tsunami eroded a lot of the coast. It pushed a lot of the sand inland. The mines and unexploded ordnance got distributed inland with the debris.

“We established a consortium of different NGOs and we raised $60 million, employed 900 staff there and did a huge range of work that went beyond demining. We were supporting people in transit camps who had lost their homes. We helped establish communities and built over 2000 permanent houses.

“Then I worked for 10 years in Geneva, as the Director of Operations at the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining, which supports capacity development of governments affected by mine contamination.

“In that role I was traveling a lot – helping national authorities put together strategies, prioritisation plans, standards and information management systems to facilitate clearance operations and promote stabilisation and development. Countries included Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Yemen, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Iraq”.

Geopolitics and demining

Guy was headhunted in 2018 to explore confidence building opportunities between North and South Korea, which included collaborative approaches to clear unexploded ordnance in the heavily mined Demilitarised Zone (DMZ).

“I was employed by Germany, who were chair of the Sanctions Committee for the UN Security Council, to design an ambitious project of confidence-building between the militaries, focusing on joint training and demining in the DMZ.

I organised a delegation of generals from the US and South Korea to come to Geneva. Separately, I met a North Korean delegation together with a retired Swiss Ambassador to China and a colonel from the Swiss army, acting in a neutral capacity. It was very exciting.”

I organised a delegation of generals from the US and South Korea to come to Geneva. Separately, I met a North Korean delegation together with a retired Swiss Ambassador to China and a colonel from the Swiss army, acting in a neutral capacity. It was very exciting.”

While the project is now on hold due to rapid deterioration of relationships between the countries, it remains a highlight for Guy, who has written and published on the subject of political, humanitarian and environmental implications of demining in the DMZ.

Rebuilding Ukraine

Guy is currently based in Ukraine, working with the World Food Programme and the Food and Agricultural Organisation.

“In Ukraine the war is ongoing and the numbers of mine victims continues to climb. Over 1,000 civilians – innocent men, women, and children – have been casualties of unexploded ordnance so far.

“In Ukraine mines are a big issue for farmers, in particular. Ukraine is the breadbasket of Europe. It’s astonishing how much the country has contributed to the global food security – for sunflower oil alone they supplied 25% of the whole world.

“So, the conflict has created problems for food security not only domestically in Ukraine, but also for the rest of the world.

“I coordinate an initiative here for these two big UN agencies. It’s all about helping farmers and households get back to cultivating their land safely and to support livelihoods and revitalisation of rural communities. Internationally, WFP also purchase a lot of grain and a lot of foods from Ukraine to deliver in Africa and around the world to alleviate hunger – so WFP can also help connect farmers with markets.

“Since February 2022 the WFP has delivered 2.4 billion meals to people in Ukraine alone. Every month we feed around 2.4 million people using convoys and local humanitarian partners to reach communities along the front lines.”

Close group of friends

Despite his international work, Guy has stayed in close contact with his fellow Southampton alumni and is grateful to have such a strong support system.

“Although I’ve travelled around the world, I have this tight knit group of friends from my time at university. This friendship and the network from Southampton has allowed me to easily drop back into the UK wherever I come from in the world.

“So many other expats get lost forever after decades overseas, but this connection allows me to come back easily. I get invited back to do sports events and socials. We’re all godparents to each other’s children.

“My work is quite different from theirs, but I’ve been able to get advice from them on business issues related to humanitarian and development work. I’ve turned to them for their experience on legal matters, management and recruitment questions. It’s a very rich source of expertise and we bounce ideas off each other frequently.”

Human impact

Looking back over his career, Guy’s proudest moments are often from those early days, before the protective gear and best practice, before the international recognition.

Looking back over his career, Guy’s proudest moments are often from those early days, before the protective gear and best practise, before the international recognition.

“I think some of the most impactful moments are the simplest. Not when you’re responsible for working with the government or with some national programme like I am at the moment, but when you’re dealing with a small project – an activity where you see the impact on a particular family.

I have a vivid memory of a woman and her small hut in Angola – there was an electricity pylon, which had been mined and the villages tried to put a fence around it, but the goats and cattle were always trying to push it down because the grass was more lush. It kept causing accidents with her livestock and fear for her with her family.

It was a very simple task to remove those mines, but I’ve never been met with such enormous gratitude: tears streaming down her face, not speaking each other’s language.

You walk away just thinking “I’m really doing what I want to be doing.”