Hartley News Online Your alumni and supporter magazine

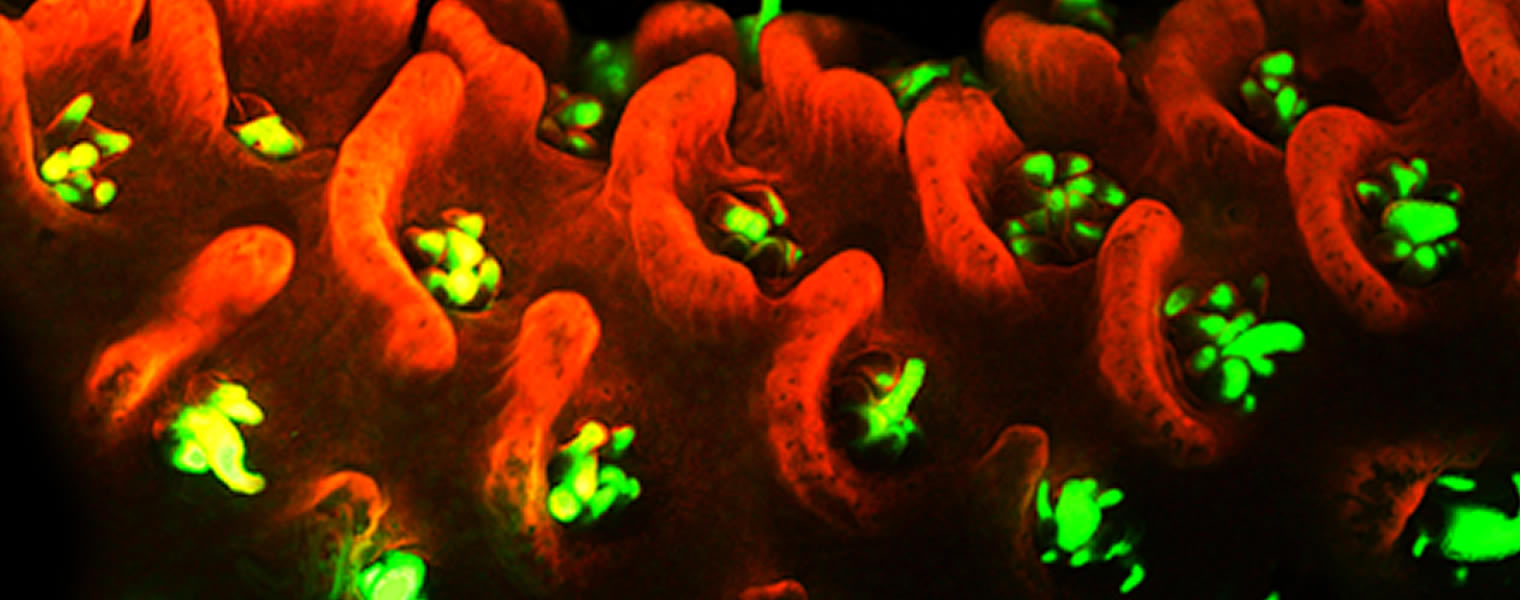

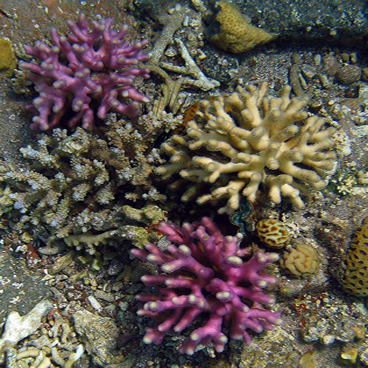

Jörg Wiedenmann, Professor of Biological Oceanography and Head of the University’s Coral Reef Laboratory and his team have discovered the genetic basis which allows corals to produce their stunning range of colours.

They have found that instead of using a single gene to control pigment production, corals use multiple copies of the same gene. Depending on how many genes are active, the corals will become more or less colourful.

Jörg says: “It was one of the longstanding mysteries of coral reef biology – why sometimes individuals of the same coral species can show such dramatic differences in their colour, despite sitting side-by-side on the reef and being exposed to the same environmental conditions. The key finding is that these so-called ‘colour morphs’ do not use just one single gene to control the pigment production, but multiple identical copies of them.”

He adds: “Corals need to boost their capacity to cope with too much sun. We show that increased light levels switch the genes on that are responsible for the production of the colourful, sunscreening pigments. The more genes they can activate, the more colourful they become.

“The genomic basis of this strategy does not only explain how colour polymorphism can increase the potential of the coral species to extend their distribution range along the steep light gradients of coral reefs, but offers also potential explanations for adaptation processes in other organisms.”

The study, which is published in Molecular Ecology, also involved colleagues from the University of New South Wales in Australia and the University of Ulm in Germany.

Click on the video below to learn more about our research into corals.