Hartley News Online Your alumni and supporter magazine

Professor George Stevenson, one of the founders of cancer immunology, was awarded an honorary degree by the University in July. Christian Ottensmeier (PhD, 1999), Professor of Experimental Medicine at the University, pays tribute to George’s pioneering career and talks about the future of cancer immunology at Southampton.

George truly deserves this accolade; he was one of the pioneers of cancer immunotherapy research and his work focused on the concept that the immune system could be steered towards fighting cancer.

In awe of an expert

George is a careful thinker, a deliberate and considered person. He is very much admired for his research but equally for his immaculate kindness and courtesy to people from all walks of life. When I came to the University as a student, I was in awe of him. He gave so much thought to how the treatments he developed might actually benefit people – and he was so willing to teach and share his thoughts. He showed by example that knowledge gained in the lab can be translated into treatments that help people. His example contributed to my own decision to specialise in transitional immunology – George’s legacy has shaped the way I think about translational medicine.

From a clinical perspective, George knew it was critical to embrace a bench-to-bedside approach, at a time when this was not yet a buzzword. He developed new antibodies and other products in the lab and then worked with Professor of Haematology, Terry Hamlin, in Bournemouth to get these tested in people. He was an early pioneer of what we now call clinical translation, and helped set the tone for this ethos at Southampton.

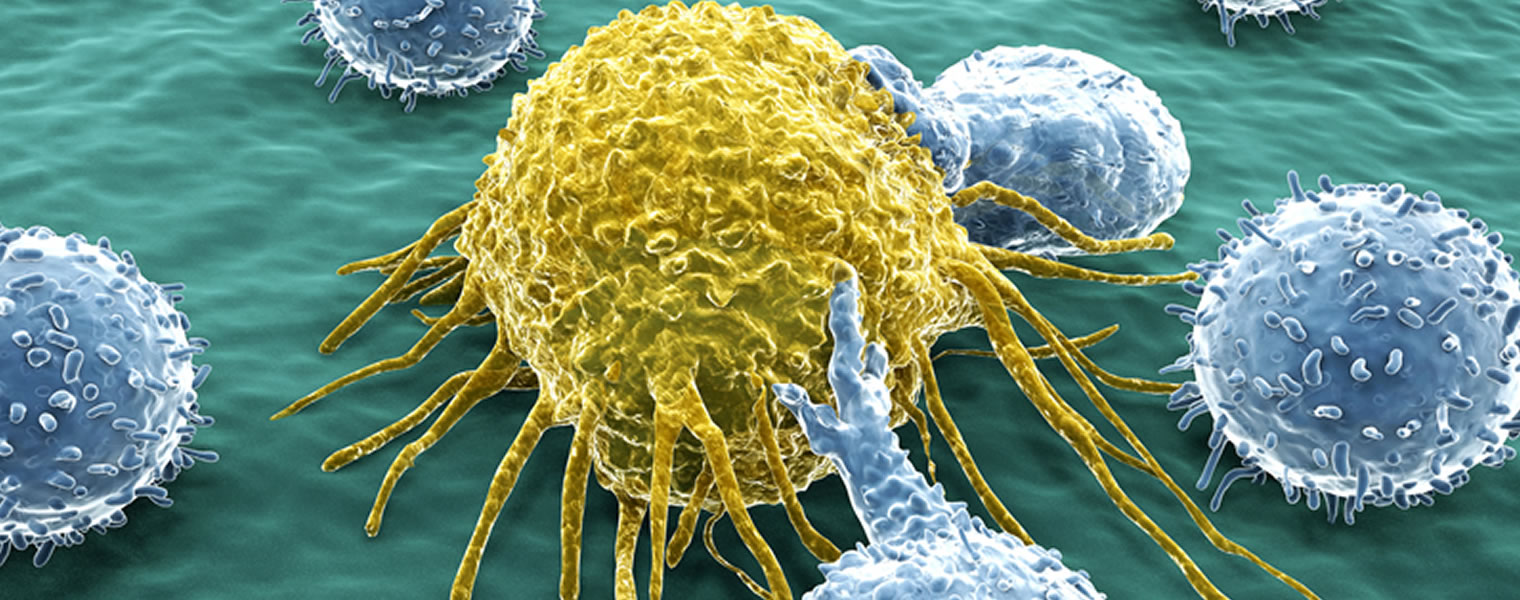

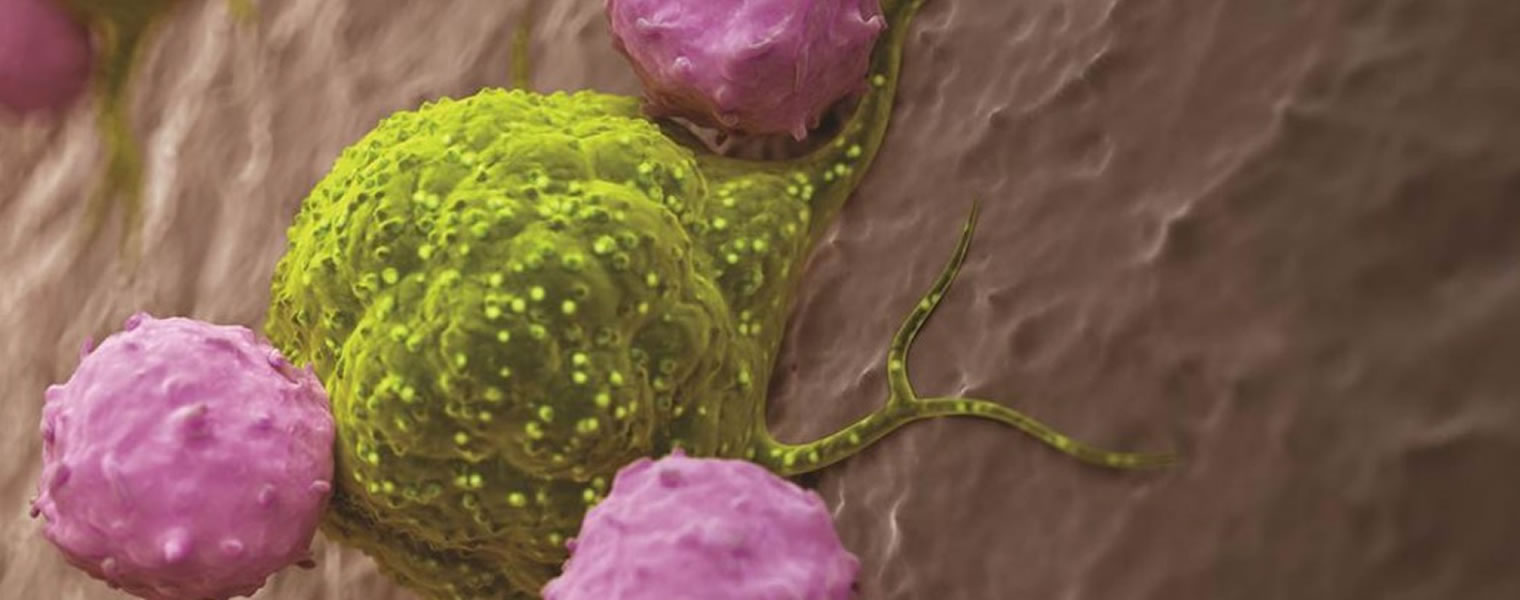

In the 1970s, when technology was not as advanced as it is now, George and his team at Southampton discovered that in each individual patient, all malignant B-cells (cancer cells) display a unique ‘marker’ protein called an idiotype. Because this marker is only present on cancer cells, and not normal body cells, it offered a precise target for antibodies produced by the body’s natural immune system. This discovery was key to opening up the field of cancer immunotherapy.

Since this early finding, the University of Southampton’s cancer immunology research has rapidly grown and is now using the immune system to fight aggressive forms of cancer, including skin, head and neck, lung and childhood neuroblastoma. Our centre has been instrumental in the development of immunotherapy drugs such as ipilimumab and obinutuzumab, which are saving people’s lives.

Shaping thinking

George’s wife, Professor Freda Stevenson, is a world-leading immunologist at the University in her own right. She has led, shaped and continues to develop groundbreaking research in understanding how the immune system might be engaged to fight against lymphoma.

For many years, cancer immunology at Southampton was synonymous with George and Freda. Their work has shaped the way the generations of cancer immunologists that came after them have thought about immunology. Without George and Freda there wouldn’t have been cancer immunology at Southampton, or at the very least it would have taken on a very different shape. Their work has set us on the road to the success we see today.

Over his career, George taught students who are now themselves world-leaders in the field, such as Professor Martin Glennie (BSc Medicine, 1977; PhD, 1980), Head of the Antibody and Vaccine Group at Southampton and Tim Elliott (PhD, 1986), Professor of Experimental Oncology at the University, and Director for the Centre for Cancer Immunology. They learnt their trade from George, while I studied under the tutelage of Freda. Indeed, we all learnt from them. It was extraordinary to see George sitting in our seminars, asking us challenging questions on areas that weren’t his main field. I really benefited from his curiosity and passion for the subject.

In 1982 George was the first person outside the USA to receive the Armand Hammer Prize, for his pioneering work with antibody drugs. This prestigious award was shared with Professor Ron Levy from Stanford. Since then, George’s work has been cited thousands of times by researchers around the world. He is one of the field’s most highly respected academics with a body of work spanning 40 years.

The go-to treatment

We have seen change in the role and understanding of immunology in the last 20 years: from a concept that could never work, immunotherapy has now become the treatment of choice. For example, in my melanoma patients we don’t often use chemotherapy anymore, as all the long-term benefit comes from immunotherapy.

Traditionally, cancer immunology has focused on the immune cells in the blood. However, my research analyses the immune cells within the tumour itself. We have done a large body of work where we characterise what the immune cells look like in the cancer, using surplus tissue available from our patients. We have learned that there are measurable features in the tumour that predict how likely immunotherapy is to work, and we are now on the brink of taking this information and acting on it.

It is really quite remarkable how Southampton experts from different disciplines work together seamlessly, from head, neck and thoracic surgeons to physicians, radiologists, pathologists, oncologists and immunologists. We are learning to ‘speak’ each other’s language and it is a tribute to our centre that this is not only feasible, but has become our working practice.

We have been fortunate enough to analyse cancer tissue before immunotherapy treatments are prescribed. This allows us to predict how the person’s immune system will react to the treatment. If we are right, then we are in a great place to make treatment choices that are more effective and less toxic.

After treatment, we then look at the cells again to check whether our predictions were correct. We are conducting several trials in this area to test this idea. Early results are promising; one patient’s cancer completely disappeared by the time they were due to have surgery to remove the tumour.

Collaboration, critical mass and variety of expertise

From a strong grounding in cancer immunology thanks to George and Freda, the future of this area is bright at Southampton. The University is currently building the UK’s first dedicated centre for cancer immunology research. The Centre for Cancer Immunology, which is planned to open in 2017, will bring world-leading cancer scientists under one roof and enable interdisciplinary teams to expand clinical trials and develop lifesaving drugs. It is being funded by the University’s £25m fundraising campaign, which has just reached the £19m milestone. Visit the campaign website to find out how to support it.

The key here is collaboration, critical mass and access to a variety of expertise: taking a puzzle and looking at it from different angles. The Centre will give us the home in which it will all be housed. And to the outside world, it will indicate that we are really committed to tackling global challenges in an interdisciplinary way.