Hartley News Online Your alumni and supporter magazine

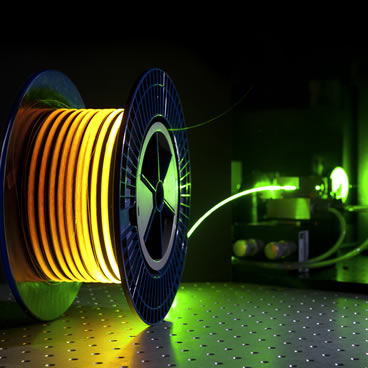

Alumna Anna Barney (BSc Physics, 1986; MSc Electronics, 1987; PhD, 1995), Professor of Biomedical Acoustic Engineering at the University, has previously analysed the speech of Neanderthals in a bid to understand our vocal past. She is now leading research that could help our future health.

Currently there are more than half-a-million people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in the UK.

In an effort to better understand the progression of the disease, Anna is leading a new study into whether speech could be used as a reliable indicator for the onset of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

It is not the first time Anna has used her skill in speech acoustics in the field of medicine having also headed up projects including studying breathing in speech as a tool for monitoring asthma, and on lung sounds in cystic fibrosis and COPD.

However, she describes her latest work as an exciting new chapter in her research career. She said: “It’s exciting, but at an early stage and needs lots of work to take it from a good idea to a reliable monitoring tool that works in clinical practice.”

Identifying differences in speech

Her latest body of work involved her team studying groups of patients shortly after diagnosis while they were talking to people who did not have the condition. By recording their conversations in a controlled environment the team was able to identify some key differences in the way the two groups managed the conversation.

The team first identified what are known as ‘conversational overlaps’. These are points in conversations where people talk over each other, for example, by trying to interject or confirming what the other person is saying while they are speaking, using words, noises or laughter.

By studying the conversations Anna found that people with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis overlapped a lot more than those without. Anna explained:

Speaking puts a lot of strain on the brain. We have to work quite hard to speak and especially to take part in conversations, so we can tell how well the brain is working from looking at how people speak.

“Alzheimer’s diagnosed speakers overlapped much more than healthy people did; they were managing the conversation less well and not judging as well when they could interrupt successfully. That can tell us that the planning part that happens in the brain during conversation is not working so well,” Anna added.

The ‘familiarity factor’

In addition, the team also found patients managed the conversation differently when they talked to people they knew when compared to talking to strangers. This ‘familiarity factor’ could prove crucial in increasing understanding of how a patient behaves in clinic, compared with how they behave at home. “That is important as it means that if we are to use speech as an indicator for the progression of the condition then we need to find a way of measuring this at home.”

Anna has also begun extending the research to investigate whether monitoring how prevalent repeated speech is, can be an identifiable symptom of the onset of the condition. Anecdotal evidence from carers and relatives suggests those with the condition often repeat a particular phrase, which again might not be evident when the patient presents at clinic.

The work has already led to promising results and it is hoped that it could lead to researchers being able to analyse the speech of Alzheimer’s patients in their own homes where a more accurate picture of how the condition is progressing using their speech can be assessed.

The research is now at a crucial stage as funding is needed for a bigger study. Anna said: “We need to find funding for a bigger study in both dementia patients and healthy subjects to characterise the speech behaviours that are typical in dementia, more closely. We need to computerise the conversation analysis so that it can be used in practice as a monitoring tool.

“Our research is not expensive to carry out. With a relatively small amount of money compared to that needed for most clinical studies we would be able to advance this work quickly to make a real difference to our ability to monitor disease progression in patients and to develop a reliable measure of how well the new developments in drug therapy are working.”