Hartley News Online Your alumni and supporter magazine

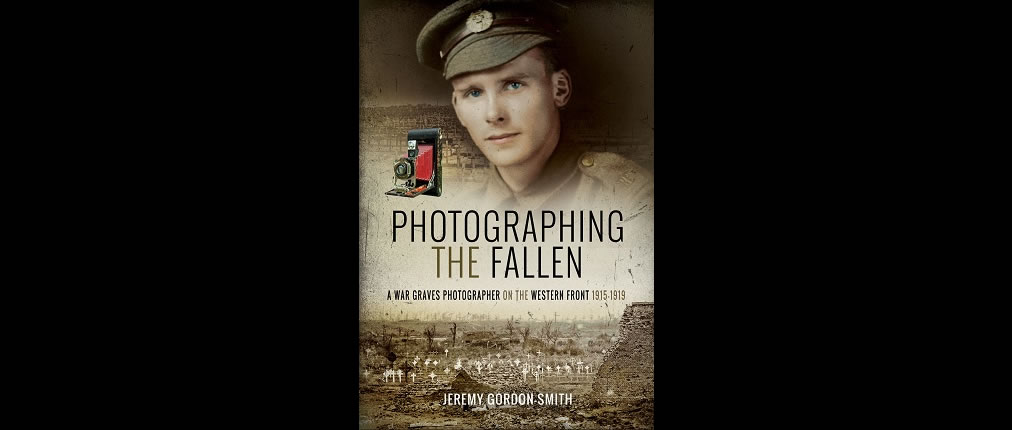

11 November 2018 marks the centenary of the end of the First World War. Jeremy Gordon-Smith (BA Archaeology, 1998) recently published a book about his great-great-uncle’s unusual service during the Great War.

Jeremy has a long-held interest in photography, genealogy, and history; he studied archaeology at the University of Southampton, which further fostered his interest in exploring the past through archives and artefacts. He now works as a therapeutic counsellor in private practice, helping people to make sense of their past and present.

To mark the centenary, Jeremy shares the story of his interest in the First World War and the journey of discovery he embarked on when compiling his book.

As far as I can remember, my interest in the First World War began in 1991 when I was studying it at school, which included a memorable trip to the battlefields around Ypres, Vimy Ridge, and the Somme. I was fascinated by the preserved trenches, concrete bunkers, and rusted shell cases that still littered the ground, as well as the enormous casualties represented by the cemeteries and memorials.

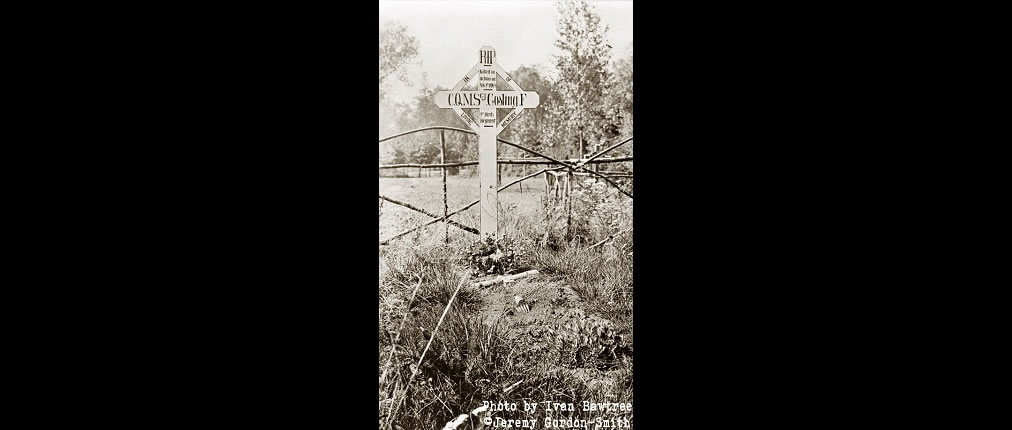

That same year, my father found the 1917 and 1918 diaries of my great-great-uncle Ivan Bawtree inside an old bureau. He gave them to me and I began to learn about Ivan’s work as a war graves photographer. The majority of his surviving collection of over 600 photographs had been donated to the Imperial War Museum in 1975, so my father took me there to view them. I was immediately captivated by the images of graves and cemeteries as they were during the war, and of ruins and devastation, particularly around the Ypres Salient, which I had just visited. There were also more upbeat photos of Ivan and comrades from the Graves Registration Unit. Twenty years later, more material came my way, and the Imperial War Museum digitised the Bawtree Collection, enabling me to compile a book.

While my archaeology course at the University of Southampton didn’t cover 20th-century conflict, it certainly taught me about burial customs and remembrance through the ages. I remember visiting sites such as the Neolithic long barrow at Avebury, a chambered tomb for nearly 50 people. My dissertation was about cup and ring marks: ancient art found on megaliths including stone circles and passage graves. Today, the war cemeteries that Ivan saw spring up across battle-scarred landscapes provide the most widespread and enduring reminder of the scale of loss and sacrifice of the Great War. Indeed, Rudyard Kipling described the construction of these cemeteries as “the biggest single bit of work since any of the pharaohs – and they only worked in their own country”.

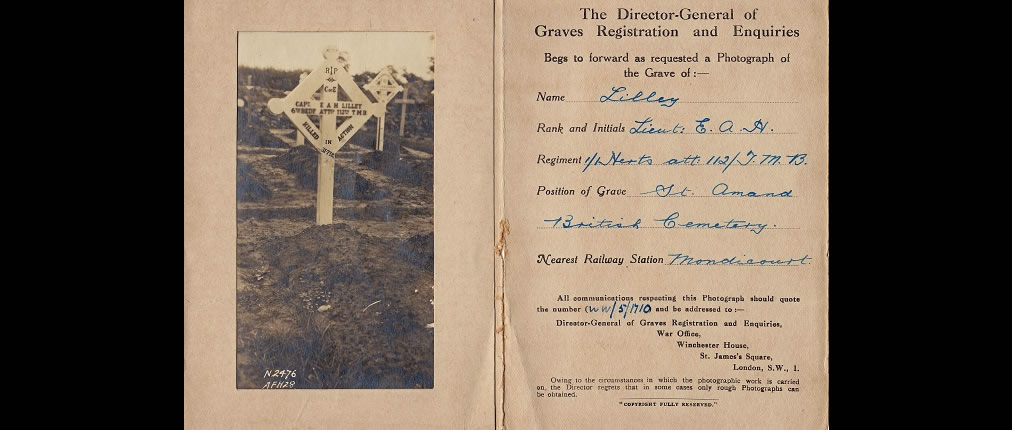

Ivan’s work was largely to photograph and record graves of fallen soldiers on behalf of grieving relatives, travelling around numerous parts of Northern France and Flanders – most notably the Ypres Salient. He was one of only three professional photographers assigned to this task, hired by the newly formed Graves Registration Commission in 1915. Ivan described the work in his memoirs:

“In France, at first we travelled in an officer’s car to various cemeteries: Bailleul, Bethune, Ypres, Kemmel, etc., but as more and more work came in, we went for several weeks and stayed at a Graves Registration Section. There we had a number of these: Bailleul, Poperinghe, Estaires, Amiens, Arras, Dunkirk, Dickebusch, etc. From those sections, we got a lift in a car when possible, but otherwise carried our equipment on our backs and rode a push bike. The more formal cemeteries were reached first by car, and then on foot through communication trenches, etc. Quite an adventure, and a certain amount of shelling as we worked close by some of our batteries. It was not always funny.”

This was pioneering work as never before had so much attention been given to the needs of bereaved relatives of war dead. Relatives were naturally desperate to gain whatever information they could about the last resting place of a loved one. In the chaos of war, information might be scant, and a soldier might be reported as ‘missing’. Graves were also lost to shellfire. Therefore, the work of the Graves Registration Unit to record the positions of graves and take photographs was extremely important as it made sure that the graves were well cared for. This not only reassured relatives at home, but was also good for the morale of soldiers at the front.

Scroll through the gallery below to see some of Ivan’s photographs:

The cemeteries tended to spring up either in close proximity to the front line or next to field hospitals and casualty clearing stations. Ivan was therefore often moving around near the front line, and was prone to shellfire. On numerous occasions, he had to run for cover or change routes:

If shelling got too heavy, the officer would withdraw us. One day, he very nearly got hit, and was bowled over while we hid behind a tree to dodge the shell splinters.

Ivan was mentioned in despatches in December 1917 for his willingness to obtain requested photos under circumstances considered ‘too lively for photography’. By the time he was discharged from service in October 1919, Ivan had taken more than 28,000 photographs of war graves.

Creating the book was a very absorbing journey, with one of the main challenges being how to manage the large amount of material at my disposal and craft it into a coherent whole. Ivan has given me a fascinating window into a tumultuous period of history, allowing me to walk in his footsteps around the Western Front. I am currently working on a second book which compiles the writings of Ivan’s sister Viola. She was a prolific diarist who provides emotive insight into life on the home front during both world wars.

Photographing the Fallen: A War Graves Photographer on the Western Front 1915-1919 was published in 2017 by Pen & Sword Books. Some of Ivan’s photographs currently feature in the Imperial War Museum’s exhibition, Renewal: Life after the First World War in Photographs, and Jeremy is also holding an exhibition related to his book at Sutton Central Library until Monday 12 November.